What's the point of a simple theory?

A story about the power of null models to shape how we interpret data.

Experimentalists wade through the murky waters of biology, hoping to tease out knowledge by controlling the things they can control and carefully observing what they cannot. In a well-designed experiment, the murky water is illuminated and an insight is reached by painstakingly ruling out other explanations. This might sound logical and systematic, but how do you know when you’re done considering reasonable alternatives? And in biology, where some truly unreasonable things can happen, how do you know what’s ‘reasonable’ anyway?

When there are many possible explanations for an experimental observation, theory can help. There are lots of ways to design a theoretical model of a biological system, and how you do it depends a lot on what you want to find out. On one extreme, very mechanistic models try to include every known biological detail to the highest accuracy possible - these models are often trying to calculate specific numbers (such as how many COVID-19 cases your region will see in the next few weeks). The type of model we’ll discuss here falls on the other extreme: phenomenological models whose main concern is capturing an interesting phenomenon, removing as much biological ‘clutter’ as possible to be sure that you really understand why things happen in your model. These models are definitely wrong, but we hope they are wrong in a way that helps us understand or rule out some of the possible explanations for experimental observations.

To demonstrate the power of simple theory to understand biology, here’s a story about a simple model we created

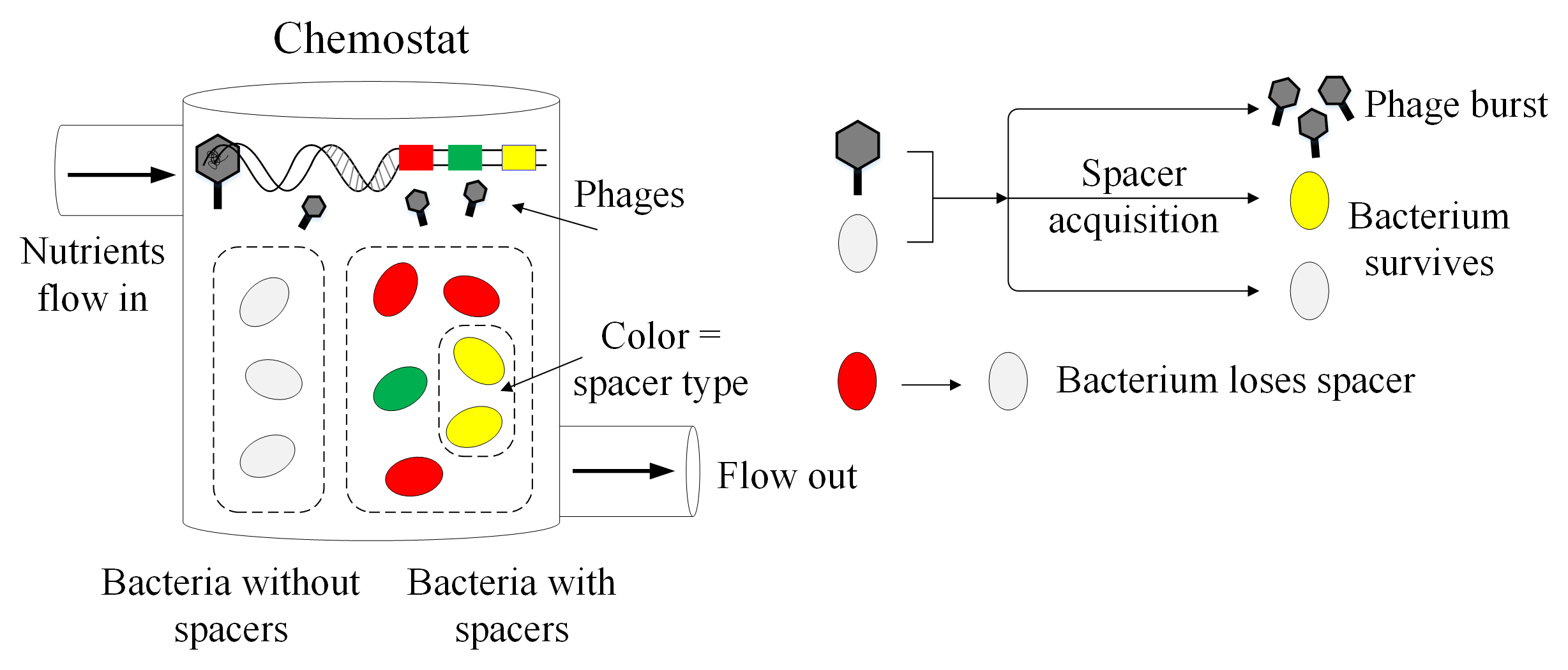

A brief introduction to the CRISPR immune system

Bacteria, single-celled organisms that inhabit nearly every environment on earth, can get the flu too. Well, not the flu exactly, but there are viruses called phages that infect bacteria specifically. If you’re a bacterium and your entire body (a single cell) gets infected by a phage, this is a big problem, so bacteria have evolved many cool ways to deal with phages.

For 60 years since the 1940s, all known bacterial immune processes could be boiled down to innate immunity: either you were born lucky with the right mutation, or you die. But in the mid-2000s, several groups near-simultaneously discovered something entirely new: an adaptive immune system that allows bacteria to gain new immunity to phages over the course of their short lifetimes

Bacteria with a CRISPR immune system can store a memory of past phage infections by cutting out small pieces of phage DNA and inserting these pieces in their own genome. The phage DNA mugshots are (unhelpfully) called spacers, and bacteria use them to recognize and bind to the DNA of phages that they’ve seen before, then neatly snip the phage DNA at that spot

Where do broad spacer abundance distributions come from?

Many different research groups have observed that when bacteria use their CRISPR immune system, some spacers end up being a lot more common in the population than others. A lot more common: in the data we analyzed for this project

This figure shows the abundance of each spacer sequence in the experiment, and each colour is a different day in the 14-day experiment. Each sequence is sorted from most common to least common (left to right) on the x-axis, and the y-axis shows the frequency of each sequence. For most days, the most common sequence at rank 1 has a frequency of 10-1 = 10%, and the least common sequences have frequencies around 10-5.

What can we learn from a spacer abundance distribution that looks like this? Does observing a broad spacer distribution tell us anything about the underlying process that created it? There are many reasons why some spacers might be more common than others. Bacteria might prefer to acquire certain spacer sequences over others, perhaps because of the way the phage genome is arranged or because of the type of proteins used for acquisition. Some spacers might be more effective than others at providing immunity, and these sequences might grow more common over time because of natural selection. Or perhaps there’s nothing special about particular sequences, and it’s some other random process that causes some to be common and others to be rare. There are two big questions here: first, can any of these processes produce a broad spacer abundance distribution? And second, if we see a distribution like this, can we draw any conclusions about what’s going on underneath? Does process A cause result B, and is result B evidence of process A? These might seem like the same question, but we’ll see that there’s a subtle difference.

Experiments can chip away at the first question. In the original study, they found in addition to this broad distribution that certain regions of the phage genome were more likely to be a source for spacers. Based on this, they concluded that the high-abundance spacers were special: their sequence makes them more likely to be high abundance. That’s one piece of evidence that spacer sequences matter, and it’s supported by other experiments. Here’s a figure from another experiment

So we’re done, right? We know why some spacers are highly abundant and others are not, and if we see a broad abundance distribution we know the cause. Or do we? We’ve answered the question “does process A cause result B”, but what about the other direction? Remember where we started: to figure out what’s going on when we observe something, we have to rule out other explanations. Could there be other explanations for a spacer abundance distribution that looks like this that would make it hard to say for sure that B is evidence of A?

Enter our null model. We modelled bacteria and phage interacting with CRISPR, and we included absolutely no distinguishing features for individual spacers: all spacers were equally likely to be acquired and all spacers were equally effective at preventing infection. This is the most boring model possible that still includes the bare bones of CRISPR immunity. We simulated this population over time, watching bacteria grow, die, and acquire spacer sequences randomly. If a bacterium had a spacer when it was infected, it got a CRISPR immune boost and was more likely to survive.

Amazingly, we found a strikingly broad spacer abundance distribution, with the most common spacers ten thousand times more common than the least common spacers. The figure below compares experimental data on the left and our simulation data on the right. Our null model shows that you don’t need special spacer sequences to find that some are very common and some are rare: you can get large differences in abundance purely because of randomness

Does this mean that the study that found high correlation between replicates was wrong to conclude that acquisition was biased? Not at all, in fact their study demonstrates that beyond a doubt! But here’s the very important catch: our work shows that if you observe a broad distribution by itself, you cannot conclude that biased acquisition is the cause, because we know you don’t need that ingredient to get a similar result. These things are all true at once: spacer acquisition IS biased, biased acquisition CAN lead to broad abundance distributions, BUT observing a broad abundance distribution does not guarantee that acquisition is biased. We have found evidence of at least two processes that can lead to broad spacer abundance distributions - biased acquisition and randomness - which means when we observe a broad distribution, we can’t know right away which is the cause.

Why does this matter? In lab experiments like those described here, you can do multiple copies of the same experiment under the same conditions to prove a result. But the world is full of important and fascinating research areas where that isn’t possible. Any study of bacteria in a natural environment is inherently irreproducible: you can never turn back the clock and do things the same way twice. So you trek to the glacial meltwater lake, sequence millions of bacteria, find all their CRISPR spacers, and plot the abundance distribution. How can you figure out what’s going on? In biology everything is going on, and the key to understanding is to figure out which of the things going on are important for what you observe and which are not. Our null model taught us that if you want to learn about spacer acquisition, you’ll need to look beyond just a broad spacer abundance distribution.